questo intervento – presentato alla 7th European Feminist Research Conference – Gendered Cultures at the Crossroads of Imagination, Knowledge and Politics, Università di Utrecht (Paesi Bassi), 4-7 giugno 2009 – rappresenta un primo stadio di un lavoro di ricerca più articolato, che si è concluso con la pubblicazione di ‘Dubbing di diaspora’: gender and reggae music inna Babylon nello special isssue di «Social Identities» intitolato Postcolonial Europe: Transcultural and Multidisciplinary Perspectives

“Shot a Batty Boy”:

Gender, Homophobia, and the Reggae Music Market in Postcolonial Europe

In the last years, the dislocation of reggae music, and its relocation into postcolonial Europe, has given rise to an international controversy about the misogyny and homophobia widespread in the dancehall yards: from Jamaica to European multiethnic cities. In this paper I will address this debate, to see how sex and power relationships are represented in reggae nowadays.

In the last years, the dislocation of reggae music, and its relocation into postcolonial Europe, has given rise to an international controversy about the misogyny and homophobia widespread in the dancehall yards: from Jamaica to European multiethnic cities. In this paper I will address this debate, to see how sex and power relationships are represented in reggae nowadays.

Spreading out from its Caribbean origins, reggae has shifted from being the cry for justice of black sufferers in the colonized countries, to being the cry for pride and redemption of black immigrants in the overdeveloped countries. It has also attracted white Europeans inspired by the critical and subversive potential of this musical genre, coming to amplify the voice of Italian youth countercultures as well.

After the Second World War, a massive emigration began from the British Caribbeans to the UK, opening the way for the incorporation of reggae music into the global economy of the multinational entertainment industry. Emigration ensured a major market to Jamaican music and the sound systems were British Jamaicans’ main means to maintain a link with the motherland. Actually, sound systems are the cheapest way to make music: all you need is a box of records and big and powerful speakers. This is one of the reasons why sound systems became so popular in Italy, several years later.

The emergence of mods, punks and skinheads (at the end of the ‘60s) represent the responses given by the white youth to the presence of a black community in England (Hebdige, 1979, p. 74). In this scene Dandy Livingston recorded Rudy, A Message To You, where the figure of the “rude boy” made its first appearance. This archetype of rebellion will pave the way for the role model of the “bad man” with a gun, who will «shot the batty boy» during the ‘90s, provoking an international debate between the advocates of singers’ freedom of speech and Jamaicans’ cultural sovereignty on one hand, and the defenders of LGBTQ rights on the other (Oumano, 2005).

The “bad man” – which embodies the antagonist of the sheriff (that Marley wanted to shot) – will also contribute to white European youth’s involvement with reggae music, because it asks for equal rights and justice, assuring that it is possible to refuse to be what the Babylon system wants you to be, and pushing you to emancipate yourself from mental slavery. Reggae voices the global ghetto youth’s claim for redemption and amplifies their local practices of resistance against the system.

The explosion of the Italian sound system culture was marked by a strong militant stance, since it arose simultaneously with the emergence of occupied social centres (at the end of the ‘80s), and the student protest called “Pantera” (in 1990). To build your own sound system meant to create a space – the dancehall yard – that was outside the rules of the entertainment industry and the “slavery” of paid work in a capitalist society: a space where you could be free and express yourself.

The explosion of the Italian sound system culture was marked by a strong militant stance, since it arose simultaneously with the emergence of occupied social centres (at the end of the ‘80s), and the student protest called “Pantera” (in 1990). To build your own sound system meant to create a space – the dancehall yard – that was outside the rules of the entertainment industry and the “slavery” of paid work in a capitalist society: a space where you could be free and express yourself.

In the meanwhile, in Jamaica there was a re-emergence of Rastafarianism and homophobia, as a consequence of what was perceived as a misappropriation of an exclusively ethnic, Jamaican style, by white people that – unlike the British youth – still hadn’t faced the presence of an immigrant community, nor of a black subculture, in their own country.

Rastafarianism had given a self-affirming identity to the migrant communities in the UK, but it has also prevented women’s participation in social and political life. The traditional Rastafarian beliefs impose many restrictions to women: they are supposed to serve their husbands and to engage in sex only for the purpose of reproduction. Any other sexual practice is forbidden, and homosexuality is considered unnatural. Given these premises, there is nothing surprising about the marginalization of women in reggae music and about the homophobic attitude of this scene.

Although women are the main topic in reggae music, the perspective is predominantly male and sexist, even if the one who speaks is a woman. Gender relationships, as they are represented in reggae music, are still grounded on a “colonial mentality” which reflects the master/slave paradigm, whether in Jamaica or in Europe. Masculinity is overemphasized – through the stereotype of the “bad man” who wants to shot the “batty boy” – as a response to the colonial strategy of feminizing the colonized men, in order to dominate them. On the other hand, women are confined to the role of mothers, in charge to embody the national language and traditions, in opposition with the colonizer country. If they transgress this role, they are considered as “bitches”.

The figure of the “mother of creation” is widespread in many songs, that ascribe women the role of building the national identity and preserving its culture and traditions, identifying female subjectivity with motherhood and the motherland. Even female singers continue to embody the same stereotypes: both as mothers, in charge of passing down the national language and traditions, and as symbols of the nation, in charge of defining the borders of Jamaican national culture after the independence from the British Empire.

Confining women to the role of mothers and wives, always in a hierarchical relation with men, the stereotype of the “mother of creation” is to sex-gender system as the “house nigger” is to the economy of the plantation: it does not reverse the power relationships inscribed in this system, rather, it contributes to its preservation.

According to bell hooks, contemporary cinema divides black women into two categories: “mammies” or “hot bitches” (hooks, 1992, chap. 4). So far I have focused on the “mammies”, now let’s look for the “bitches”. According to Linton Kwesi Johnson, «Inglan is a bitch/dere’s no escapin it». In this classic about the difficulties incurred by Jamaican immigrants entering the British labour market, he uses a sexist derogatory term to define the colonizing nation. But doing so, he reverses the gendered parental rhetoric of colonial rule, consisting in a «maternal model of caring for the welfare of indigenous people» and a «paternalistic model of the rigorous disciplining of native children», both used as a strategy to infantilize and feminize the colonized in order to dominate them (Gouda, 2001, pp. 11).

Europeans had always «emasculated» the colonized men, who consequently responded by enhancing the manly prerogatives associated with the masters. The Jamaican tradition of toasting has focused on the glorification of the “big bamboo”, overemphasising the virility of the male performer with a representation of hyper-masculinity that is in step with the representation of women as sexual objects.

But what happens when one woman consciously acts and performs as a “bitch”? Jamaican singer Lady Saw sings sexually explicit lyrics with her hand touching her vagina, or straddling one of her male fans. She has been criticized for the “slackness” of her language and gestures, but we should interpret her use of the body on the stage as a way to ironically mime the hyper-masculinity of her male counterparts, reversing it in a celebration of hyper-femininity.

The nationalist ideology expressed in reggae attributes to women specific functions: mothers, reproducing the nation’s population; keepers of traditional culture; and symbols of the nation (Hill Collins, 2006, p. 17). But it also provides a role model for masculinity: men are supposed to defend the nation as well as their own families, which consist of heterosexual couples. Thus, the existence of homosexuality challenges the entire system of race, gender, nationality and heterosexism, which popular music is supposed to reproduce and support.

An apparent distinction between Jamaican reggae and its diasporic forms emerged after the explosion of the controversy over homophobia, starting with Buju Banton‘s release of Boom Bye Bye in 1993, and renewing with his charge of beating a gay man in 2004. In this song the Jamaican singer incited to kill homosexuals with a gun shot («boom bye bye on a batty boy head»), voicing the homophobic attitude widespread in Jamaican culture, where homosexuality is considered a crime, that can be punished with ten years of hard labour. So the pressure on the Jamaican government to change this law, by Western organizations, has been perceived as an imperialist intervention against the island’s cultural sovereignty, as if they are pretending once again to civilize a Third World country incapable of self-determination.

To understand how sexual relations are represented in reggae music today, it is necessary to recognize the «two cultures [that] were boiling in the Caribbean» during the days of slavery: «one of domination», carried out by imposing Christian religion on black slaves, evoking the fire of Sodom and Gomorra; and «a culture of resistance», Rastafarianism, developing from African roots and the refusal of Western values, paradoxically identified with another biblical image, the Babylonian inhabitants as the representation of absolute immorality (Campbell, 1985, p. 19). Even if reggae music cannot be entirely identified with Rastafarianism, lyrics have always been informed by biblical language and Rastafarian faith. Since contemporary stars of Jamaican reggae are mostly Rastafarians who invoke the biblical fire to “burn” all homosexuals, I would argue that Rastafarianism, initially arising as a strategy of resistance against colonialism, revealed itself to be a fundamentalist religion, which continues to oppress, rather than freeing our minds. Using the Bible, the tool of colonial power, could allow the Rastaman to temporarily beat the master at his own game, but could not enable him to bring about a genuine change, «for the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house» (Lorde, 1984, p. 112).

Reggae musicians used the stereotype of the “bad man” from the ghetto to nourish the cult of virility and affirm the superiority of the black male. According to Malcom X, the regaining of virility by black men was a means to revenge against the historical castration they suffered during slavery. These beliefs, rooted in the experience of the plantation system, have converged in reggae music.

Only one Jamaican singer was able to challenge the colonial assumption that black sexuality must be based solely on «power relationships which mirror master/slave paradigms» (as wished by bell hooks, 1992, p. 74), releasing a song against homophobia. In Do you still care, Tanya Stephens compares the bushings undergone by gays in Jamaica with the KKK’s hangings of black people, suggesting that racism and compulsory heterosexuality are two systems of power which reinforce each other.

Only one Jamaican singer was able to challenge the colonial assumption that black sexuality must be based solely on «power relationships which mirror master/slave paradigms» (as wished by bell hooks, 1992, p. 74), releasing a song against homophobia. In Do you still care, Tanya Stephens compares the bushings undergone by gays in Jamaica with the KKK’s hangings of black people, suggesting that racism and compulsory heterosexuality are two systems of power which reinforce each other.

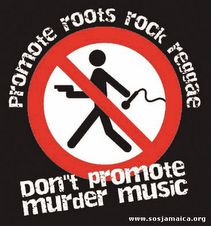

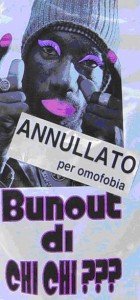

When Italian reggae followers realized how much brutality was coming out from their icons’ mouths – supposed to spread positive vibes – the international protests had provoked the cancellations of concerts in Europe and in the US, the denial of visa to Jamaican artists supposed to perform in Europe, their exclusion from the Mobo Awards, and from the I-tunes catalogue.

Even if anti-gay lyrics are the easiest way to get enthusiastic approval from a Jamaican audience, one could argue that inciting to kill gays in white postcolonial Europe is not acceptable. But this would only reproduce a racial and cultural binary. Even if European reggae followers state they are not homophobic, they continue to justify their heroes because of colonial exploitation, or they refuse to face the issue directly because Jamaican language is difficult to understand and they only enjoy the riddim.

In 2007 I was involved in a campaign to boycott homophobic reggae, that drew criticism from many reggae followers, who perceived it as a form of censorship. Only one Italian reggae band, Radici nel Cemento, supported the campaign, releasing a song titled Siamo tutti omosessuali (We are all homosexuals), where they condemn homophobia, reminding that the celebration of “Italian virility” was a legacy of the Fascist Empire.

In 2007 I was involved in a campaign to boycott homophobic reggae, that drew criticism from many reggae followers, who perceived it as a form of censorship. Only one Italian reggae band, Radici nel Cemento, supported the campaign, releasing a song titled Siamo tutti omosessuali (We are all homosexuals), where they condemn homophobia, reminding that the celebration of “Italian virility” was a legacy of the Fascist Empire.

But my point is that homophobia is not confined to right wing mentality: it also affects Italian left wing activists, which usually accept uncritically the macho and aggressive attitude of rappers and reggae singers. This is because the “bad man” from the ghetto has become a role model for social movements’ activists, which had never questioned their own machismo and homophobia. Since the “bad man” belongs to the working class, he is a revolutionary, so we are all supposed to feel solidarity with him and we must accept him as he is, without any critical reflection – even when he preaches to “shot a batty boy” (Marcasciano, 2007, p. 102).

Even if social centres are supposed to be spaces where people are free to express themselves – and even if European reggae followers cannot hide themselves behind the shadows of colonialism (since they have been colonizers, rather than colonized) – no reggae follower, in Italy, could easily assert to be exempt from sexism and homophobia. Contemporary reggae music in Italy, which for years has been the soundtrack of political demonstrations, now shows all its limits: promoters and consumers are not interested in experimenting, transforming and desiring; they limit themselves to aping Jamaican attitudes, reducing this musical form to another product to market for Western consumption.

When reggae music emerged in Italy, it was perceived as a form of “exodus” from capitalism – from the careerism and the competition of the musical market – as a way to create new aesthetic forms and to build a new sense of collective belonging. In this sense the Italian reggae scene possessed all the features of a “counterculture”: an explicit political opposition to the dominant culture, an attempt at building alternative “institutions” (self-organized social spaces, underground reviews, record labels, distributions), and an ability to blur the distinction between work and spare time (Hebdige, 1979, p.148). Now that these countercultural phase is over, and reggae has gone mainstream, becoming a business, it is clear that the Italian reggae audience has always identified with a music and a lifestyle, without confronting the material and historical conditions of its production. In this process of appropriation and consumption, the reggae audience and promoters can sing anti-racist lyrics, without addressing their own racism, and they can say they are not sexist, while playing homophobic records.

When reggae music emerged in Italy, it was perceived as a form of “exodus” from capitalism – from the careerism and the competition of the musical market – as a way to create new aesthetic forms and to build a new sense of collective belonging. In this sense the Italian reggae scene possessed all the features of a “counterculture”: an explicit political opposition to the dominant culture, an attempt at building alternative “institutions” (self-organized social spaces, underground reviews, record labels, distributions), and an ability to blur the distinction between work and spare time (Hebdige, 1979, p.148). Now that these countercultural phase is over, and reggae has gone mainstream, becoming a business, it is clear that the Italian reggae audience has always identified with a music and a lifestyle, without confronting the material and historical conditions of its production. In this process of appropriation and consumption, the reggae audience and promoters can sing anti-racist lyrics, without addressing their own racism, and they can say they are not sexist, while playing homophobic records.

While Jamaican labels release records palatable for their target – because the homophobic lyrics have been censored – the majority of white European followers can freely consume this “exotic product” without a critical comprehension. Through adapting a particular aesthetic form to their own specific experience, they would have been able to transform themselves from consumers into producers of their own subjectivity. On the contrary, they only reify people and cultures into exchangeable aesthetic objects. But this “exotic product” still has much to reveal about its own consumers.

References

- Campbell, H. (1985). Rasta and Resistance. London: Hansib.

- Gilroy, P. (1993). The Black Atlantic. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University.

- Gouda, F. (2001). What’s to be done with gender and post-colonial studies? Amsterdam: Vossiuspers UvA.

- Hebdige, D. (1979). Subculture. New York, NY: Metheun.

- Hill Collins, P. (2006). From Black Power to Hip Hop. Philadelphia: Temple.

- hooks, b. (1992). Black Looks. Boston: South End.

- Huggan, G. (2001). The Postcolonial Exotic. London: Routledge.

- Lorde, A. (1984). Sister outsider. New York. NY: Crossing.

- Oumano, E. (2005, February 8). Jah Division: Free speech, cultural sovereignty and human rights clash in reggae dancehall homophobia debate. Village Voice.

- Marcasciano, P. (2007). Antologaia. Milano: Il dito e la luna.